Reflecting on the last six months of roasting styles at The Crown.

For as long as we’ve been serving coffee, The Crown’s menu has featured a revolving door of fresh and seasonal coffees served across a number of brewing styles. By far, our most consistent outturns (aside from cold brew in the warmer months) are two single-origin espressos, and a light and dark roast option of two single-origin batches brewed drip coffee. The choice of an all single-origin menu is meant to shine a light on the source – the people, places, and processes that shape its character. It also highlights the role of the Royal as an importer, offers an array of tasting possibilities, and highlights some of our favorite Crown Jewels.

In August of 2021, I found myself thrust in front of the roasting machines. With some ten years or so standing between myself and my most recent experience at day-in-day-out production roasting, I necessarily leaned heavily on my colleagues – from The Crown’s two former Roasting Directors, Jen Apodaca, and Candice Madison, I’d learned an immense amount by watching and listening to their styles and approaches.

Distilled in the absolute simplest of terms, Jen’s roasting had always been driven by an obsession with coaxing out sweetness above all else, and Candice’s styles were shaped by a conviction that consistent target end temperatures and total avoidance of baked flavors would produce the tastiest results. Our Cropster account is swollen with the evidence of practicing these theories – a trove of data I’m lucky to have at my fingertips.

Another stroke of luck, Production Assistant Doris Garrido’s apprenticeship under both titans of coffee toasting bore fruit in the form of a well-honed and capable machine operator, with the rare gifts of rampant curiosity and an exceptional palate. Together we mapped our roasting days, cupped our results, and started getting comfortable with the operational idiosyncrasies of our little Diedrich IR-5, which we began to quickly outgrow as service resumed post-lockdown.

Our biggest initial challenge would be to scale espresso roasting to the 15kg capacity Loring Falcon. Initial trials (and errors) on the machine focused on transferring two key metrics in our existing roast profiles: Maillard percentage, and time after the first crack, which leads to one of my first takeaways for espresso.

Espresso Roasting – Expressing Nuance through Exhaustive QC and Roasting

At the height of Zoom-fatigued pandemic isolation, an assembly of Crown espresso enthusiasts hosted a webinar simply entitled “Good for Espresso.” About halfway through, Alex Taylor, former Tasting Room Manager, and current Inbound Traffic specialist hit me with a retort I’ll never forget.

I’d posited, quoting an adage I’d been taught during Kyle Glanville’s days at Intelligentsia, that “good coffee makes good espresso.”

Without disputing the notion that quality ingredients are a key component of high-quality extraction, Alex’s response was that “good baristas make good espresso,” underscoring the work of the craftsperson operating the espresso machine. I think a logical extension of this idea may be to include the craftsperson at each stage of a coffee’s life cycle, from farmer to processor, roaster and QC specialist, and of course the barista’s hands which shape the final beverage.

With skilled baristas and a great green coffee, it fell to Doris and me to craft delicious roasts. Espresso quality control for me still always starts at the cupping table, unpacking the coffee in a ritualized format in the company of respected peers.

While all roasts must eventually be brewed, espresso’s unique challenge is its concentrated brew ratio and the widely acknowledged need to rest the beans to off-gas and prevent unmanageable crema. The longer delay between cupping and brewing feedback can put a strain on even the best sensory recollection, while pressurized high-concentration brewing methods may highlight flavor eccentricities (like acidity or age) and suppress nuance (like florals or delicate fruit notes).

During our profile transfer experiments, it became clear that the Loring’s ability to turn coffees around and exit the early drying stage in roasting quickly would necessarily reconfigure our ideas about roast stage percentages. Taking a page from noted Loring expert Rob Hoos’ book, Doris and I began to focus on stretching the middle stage of roasting from the beginning of the color change to the beginning of the first crack – a phase commonly referred to as the Maillard Reaction. Doing so has the tendency to highlight sugar-browning flavors, improve perceptible viscosity, and manage the acidity of especially wild coffees.

One of our first early successes was a pretty dramatic example in the form of a natural Costa Rica from Coopedota’s El Vapor. In the roast chart below, the original blue Diedrich profile can be contrasted with the red Loring roast. A significant improvement we achieved with the extended Maillard phase on this coffee was spending 30 seconds less in total development time after the first crack but ending with a slightly darker internal Colortrack number, which allowed us to preserve a little of the inherent sweetness and acidity while still roasting the coffee sufficiently beyond any underdeveloped flavors. These qualities were supported by ample viscosity and sugar browning from the long color change stage, lending additional complexity and balance to the cup profile.

The success could be measured at the cupping table in attribute scores, but it was truly realized in shots pulled by talented baristas. The ability to taste both and understand the tastes which are created and altered in the roast is the key to unlocking this skill. Recognizing which fruit and acid profiles persist in the espresso, and how and why they were roasted is a talent best reinforced by repetition and experience.

A Balanced Approach to Drip Roasting

Balance, when I first started hearing and then repeating the term, was a sensory category… but also a stylistic choice. At a time when many roasters were doubling down on light roasted, acid-forward washed coffees as the crux of their identities, “balance” became a synonym for “boring” in some circles.

For others, including myself, it was about achieving a kind of “both/and” quality to a coffee. Could I roast a screamer of a grapefruity Kenya in a way that had a sweet cherry or blackberry note and an elegantly clean finish? Could I boost the floral flavors of a lemony Ethiopia to achieve harmony and unmatched complexity? Could I source brilliant mandarin-like Burundis that also had a silky mouthfeel?

Light Roasts

Light roasting for drip coffees can take on many forms depending on the coffee. While I admittedly love white-knuckle roasting with high heat and open airflow with nothing but your trier to tell right from wrong, there’s a subtlety that’s often lost in coffees that fly out of the first crack too quickly.

For that reason, I’ve been trying to find balance in many of the coffees that we roast for light batches or pour-overs in the final moments of roasting. For a reason I’m not fully able to explain, I really want my light roasts to spend close to 90 seconds of development after crack. In many roasting environments, I’ve seen, this will squarely push coffees into the “Medium Roast” territory. Thus, keeping things on the light side in this paradigm can require a little finesse.

My strategy is this: hit the gas early, well before the turnaround. Get out of the drying phase quick and start slowly, incrementally pumping the brakes in color change. Ideally, I want to get to the first crack fairly quickly still – under 8 minutes if possible, and I’ll take less where I can.

That said, I don’t want to steamroll it: by the time the coffee is cracking regularly (when I mark the first crack as it begins to roll, less than 1 second between pops) I’m shooting for a rate of rise at 15F/minute or below, with a decline of at least 5F every thirty seconds thereafter. For the math whizzes, that means that by 60 seconds of development I should be at or under 5 degrees of positive heat delta per minute, and I should be finishing my roast just as the RoR equals zero.

Some folks might describe this as a “crash followed by baking” but I’d look them in the eye and pour them a cup and tell them not to knock it before they’ve tried it.

What I’m trying to achieve is a light color that also has that kiss of caramelization, maybe borrowing a theory from Jen (though I’m certain I’m roasting differently than she is). This has the additional effect of balancing any extreme acids without suppressing them. Instead of roasting them away, I’m trying to develop complexity, clarity, and sweetness alongside the brightness.

Coffees behave as if they’re exothermic briefly at first crack anyway; that’s how they want to roast. If I’m not taking a roast very far in color (say 52-54 ground Colortrack, maybe 70+ on the old Agtron gourmet), I can coast there on the wings of sufficient momentum built up in the early stages.

Here are a couple of examples:

The blue roast is a Loring profile of a natural Ecuador – this is Doris’ profile; I’ve unfortunately influenced her terribly. Note the massive RoR crash. What a great coffee, you should come to try it.

The red roast on the Diedrich is a washed Peru (less distinctively crashed) and the profile spends a lot of time in the drying stage because that’s how Diedrichs are built to roast. So, as I learned ages ago from an old friend (Christian Rotsko, currently Director of Green Coffee at Merit) we work within the constraints of the equipment and the tendency of the bean. Despite these boundaries, we still end up with basically the same endgame: roughly 90 seconds of low-followed-by-lower Rate of Rise for a cute tasting light roasted pour-over.

One thing that’s pretty wild about the super low rate of rise at the end is that I can practically ignore end temperature goals if I’m on track with time and rate of rise. In fact, I haven’t been able to fully automate a profile roast on the Loring in this roasting style because it drops the batch 30-60 seconds prematurely. I love the machine and its capabilities but there’s clearly no substitute for a skilled operator in some cases.

Dark Roasts

Admittedly, when I think about crafting my own “dark” roasts I’m usually conceiving a coffee that has just barely reached the beginning of the second crack. This is not a dark roast for true believers, but rather a compromise for coffee drinkers who prefer not to be assaulted by lighter roasting styles. In my experience, modern specialty roasters (including myself some years in the past) may choose to feed these “compromise” dark roasts with past crop leftovers or unloved blenders, and then relegate them to second class status when developing roasting styles.

Roasting in Oakland – which borders Berkeley, which birthed the first Peet’s Coffee – carries with it a long and entrenched dark roasting legacy that looms quite large. A lot of these Berkeley dark roasts are, to use local parlance, “hella dark” and really don’t taste much like anything but char. And that’s all perfectly fine but not exactly what I’ve been hoping to roast and serve at The Crown.

When I first started roasting our darker offering, my hope was to find a way to caress a roast through post-crack development, maintain a degree of its inherent character, but also have that signature roast character and big body… but with sweetness instead of bitterness, rounded edges instead of jagged ones.

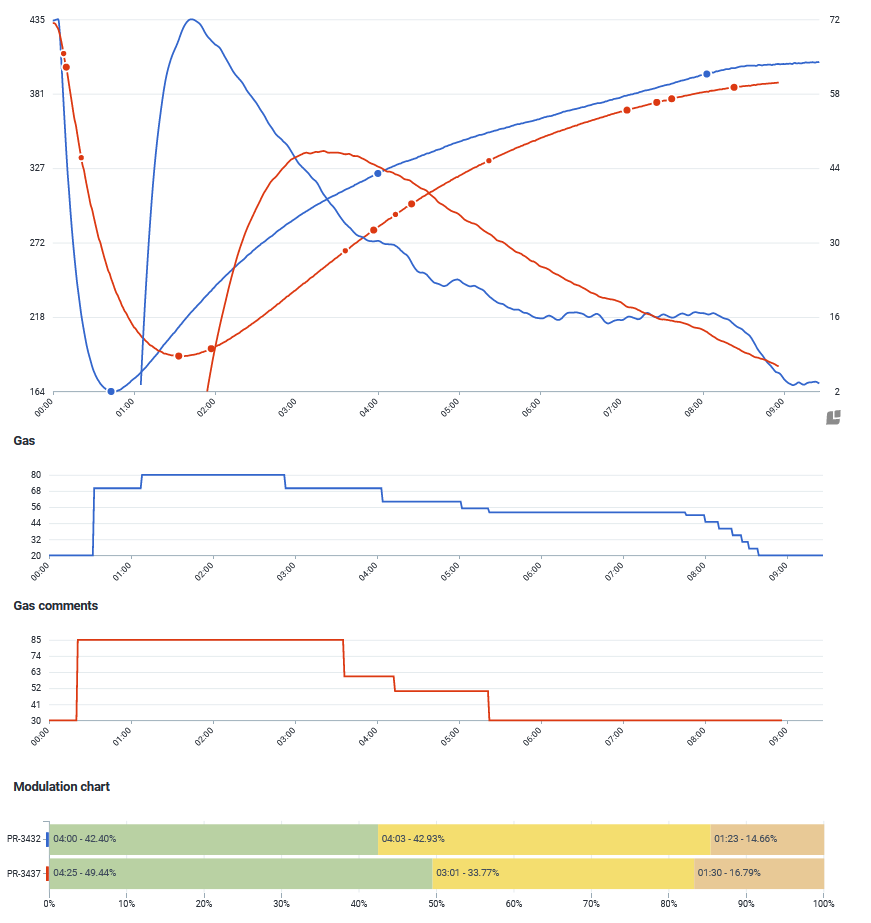

Initially, to accomplish this, my early Diedrich roasts focused on creating a long-end game that would effectively make an equal parts roast in ratios. The other key ingredient was to employ an old airflow technique I’d learned but never actually executed called “aroma roasting,” wherein smoke would be trapped in the roasting chamber by essentially choking the airflow after the first crack. You can see it graphed below, against a Loring roast in the backdrop (more on that in a moment).

At roughly 90 to 120 seconds after the beginning of the first crack, just beyond the time, we’d usually plan to drop a lighter roasted batch, we pull back our airflow to 50% on the Diedrich. This late in the roast, our burner setting is usually idled or close to it, and the airflow baffle helps retain smoke and heat in the drum. Using conserved and exothermic energy rather than pushing a bunch of new energy into the system helps to gently push the coffee forward towards a darker hue. The delicate touch to darker roasting – extending our development time after crack to about 4 minutes – allows for a perceptible increase in the body of the coffee when brewed and prevents potential late-roast scorching which is (in my opinion) a common cause of overly bitter dark roasts.

This style worked well for us using two different Central American coffees (single-farmer lots of an FTO Guatemala Huehuetenango, and an Organic Nicaragua) and as customers began to catch wind of its drinkability, our volume gradually increased.

By spring of 2022, we were ready to scale up to the 15kg capacity Loring for efficiency’s sake. However, the Loring has a dramatically different airflow system, scrubbing and recycling hot air through its powerful burner. In this relatively closed system, one way to introduce ambient air from the room into the roaster is to initiate an “air cooling” cycle.

This process ramps the burner up to 100%, increases the fan speed and opens a “purge gate” which allows clean air to enter the roaster and traps the roaster’s air throughput in the cyclone, where smoke and particulates are incinerated before being pushed out the exhaust stack. I spoke with Scott Robinson, Loring’s Special Projects Engineer, who confirmed an interesting fact: because the Loring is essentially a closed system, it’s designed to have very little oxygen in the roasting environment, “if the burner is tuned right, then it is likely there is zero O2,” he told me. Opening the purge gate oxygenates the roasting chamber, which may improve coffee aromas by oxidizing sulfur groups and preferentially “encouraging the Maillard reaction to form pyrazines… associated with nutty aromas, balancing the aroma profile,” (emphasis mine) according to Anja Rahn, Ph.D. in her Jan/Feb 2022 Roast Magazine article “Reflecting on the Art Behind the Science of Coffee Aroma,” citing research by Dr. Alexia Gloss and Dr. Samo Smrke from Prof. Dr. Chahan Yeretzian’s group at the Coffee Excellence Centre at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences.

The effect on the coffee is, according to Rob Hoos’ document for Loring, to “lower the change rate of the coffee at the end of the roast, and begin to reduce and manage the smoke coming off of the beans.” However, it does not fully halt exothermic reactions, or what Hoos refers to as “thermal momentum” in a batch of beans, despite the clearly observable crash in RoR and bean temperature probe in the graph below.

It’s basically an inverted version of the mechanics on the Diedrich. But it works. We dialed this roast over the course of a number of batches to give us a rich, full coffee with enough sweetness and body to please the picky dark roast drinkers (me, for example), enough of the coffee’s inherent character to showcase the quality of the green, and enough of a smokey edge to be considered a dark roast without having developed too deeply into the second crack.

Final Thoughts

I suspect these roasting styles will continue to evolve as we relentlessly refine our efforts. We benefit from a relatively small scale of production, which allows ample time for us to cup, analyze, and revisit roasts as we pursue excellence in coffee roasting.

Balance isn’t necessarily our only or even primary goal for all coffees. But it is an important element of how we craft many of our favorite roasts. I think one of its primary benefits might be related to accessibility – for people of many preferences in flavor and service style – to enjoy the coffee we set before them. It helps to shed the pretense sometimes associated with “fancy coffee” and allows us to offer coffees that are both easy to appreciate and simultaneously complex and riveting.

Thank you for this thorough article. I picked up several useful tips that can apply to my home roasting on a 1 Kg North propane drum roaster. I’ve also posted a link to the article on Home-Barista.

https://www.home-barista.com/roasting/chris-kornman-at-royal-crown-jewels-on-searching-for-balance-in-roasting-t79800.html

Great stuff CHris. I am more than a little jealous that your situation nont only allows but encourages yuo to “play” so much.

I particularly appreciate the way you don’t just “telll us what you did” and drop a graph below it. Insead you explore your thinking, and that of others, (you cite three of the best anywhere) getting into the chemical changes and how they vary based on different time/temp/RoR factors. You have given me some good experiments to try on my own equipment.. I do my creative roasting on a US Roasters one pound drum sample roater, gas fired. I think the first “new trick” I’m gonna try is to shorten the tornaorund phase. I typically will target 2:00 for turnaround then rise with signficant heat up toward crack. Think I’ll start playing in the 1:00 to 1:30 range, keep charging forward partway through runup to crack, slowing signficantly by halfway there.

Once I get that under control I can then begin to play with the post-crack phase. I particularly an imterested in your descriptions of going darker but with rapidly decreasing heat application, taperiing off to finish.

Fun stuff. Now WHERE am I gonna find the TIME to playlike this? Looking forward to some new refining some new tricks yuo have put into my bag. Thanks.

Great stuff, Chris.

We’ve tread this same ground, but your thoughtful inventivness is an inspiration to take a fresh look at the way we think about coffee.

We’ll look forward to your next post.

Steve

Mill City Roasters

Minneapolis, MN